Suspension bridges represent one of the most elegant and efficient structural systems ever created by engineers. Their main cables carry pure tension, with almost no bending moment — a configuration that achieves maximum strength with minimal material.

To understand why, let’s start with something simple.

The Power of Tension: Why Pulling Is Stronger Than Bending

Imagine holding a chopstick. It’s easy to snap it with your hands — that’s bending at work. But try pulling it from both ends; it’s nearly impossible to break. Most materials perform much better in tension than in bending.

Another everyday example is a clothesline.

A clothes rod bears weight through bending, requiring a thick and heavy bar to avoid breaking. A clothesline, however, is a thin cable that supports the same load through tension. It may sag under weight, but it rarely fails.

That’s the secret of structural efficiency:

👉 The more bending you eliminate — converting loads into pure tension or compression — the lighter and stronger your structure becomes.

From Beams to Cables: The Evolution of Bridge Structures

To understand why the suspension bridge is so efficient, let’s look at how bridge structures evolved over time — from simple beams to elegant cables.

Beam Bridges: Simple but Inefficient

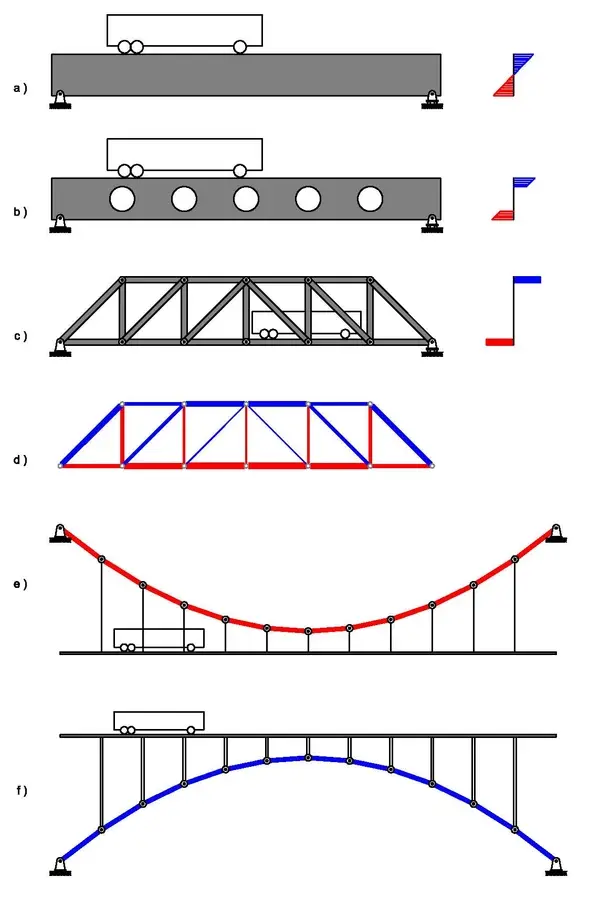

It’s like a horizontal stick supported at both ends as shown in figure a. When a load is applied, the beam bends: the top side is compressed, and the bottom side is stretched.

If you look at the stress distribution, you’ll find that:

- The top and bottom surfaces carry most of the stress,

- While the middle part does almost nothing.

That means the material in the center adds weight but doesn’t help much with strength. It’s like a bucket where only the shortest plank limits how much water it can hold — once the top or bottom fibers reach their limit, the entire beam is at risk.

Beam bridges are simple and widely used (for small roads, overpasses, and subways), but they rely purely on bending, which makes them structurally inefficient.

Open-Web Beams: Removing What’s Not Needed

If the middle part of a beam carries almost no stress, why not remove it? As shown in figure b

That’s the idea behind open-web beams — they keep the top and bottom parts (where tension and compression occur) but eliminate the low-stress material in between.

This design reduces self-weight without sacrificing strength — a small but smart improvement.

Truss Bridges: Turning Bending into Tension and Compression

Engineers took the same idea further and developed truss bridges as shown in figure c&d.

By arranging straight members in triangles, they transformed bending forces into pure tension and compression along each bar.

In a truss bridge:

- The upper chords are in compression,

- The lower chords are in tension,

- And the space in between is mostly empty — no wasted material.

A famous example is the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge in China, which uses this structure to achieve both strength and material efficiency.

Suspension Bridges: The Ultimate Form of Efficiency

If we keep pushing this optimization even further — removing every part that doesn’t carry force — we finally arrive at the suspension bridge.

Here, the main cables carry only tension, evenly distributed along their entire length.

All the bending moments disappear, leaving a pure tensile system that’s incredibly light and strong.

Think of it like a clothesline holding several shirts — the cable sags in the middle but each point is in pure tension, and the load is balanced at both anchored ends.

Arch Bridges: The Opposite — Pure Compression

On the other side of the spectrum lies the arch bridge, which works in pure compression instead of tension.

It’s elegant and strong, but there’s a catch: compressed structures can lose stability easily.

For instance, you can step on an empty soda can — it’s hard to crush at first, but it quickly buckles once it’s slightly deformed.

That’s why, although arches are efficient, they’re not as stable or lightweight as suspension bridges.

Among these, suspension bridges reach the ultimate level of structural efficiency. Every cable is in tension, and almost no material is wasted.

Why Suspension Bridges Have Their Unique Shape

Why do suspension bridges always have that elegant, curved shape? The answer lies in simple physics and geometry.

Take a chain or bicycle chain, fix both ends, and let it hang freely — it forms a catenary curve, shaped by its own weight.

You can even find this shape in spider webs, which naturally follow near-catenary curves to balance tension.

However, in a suspension bridge, the main cable supports not just its own weight but also the uniform load of the bridge deck.

When the load is uniformly distributed along the deck, the cable no longer forms a catenary — instead, it takes the shape of a parabola.

In short:

- A cable under its own weight → forms a catenary.

- A cable under a uniform deck load → forms a parabola.

This parabolic curve is not just beautiful — it is the most efficient form for the bridge to carry loads.

Every part of the cable experiences equal tension and no bending moment, allowing the bridge to span great distances with minimal material.

How the Ideal Shape of a Suspension Cable Is Formed

Let’s assume we have a suspension cable that carries a uniformly distributed load.

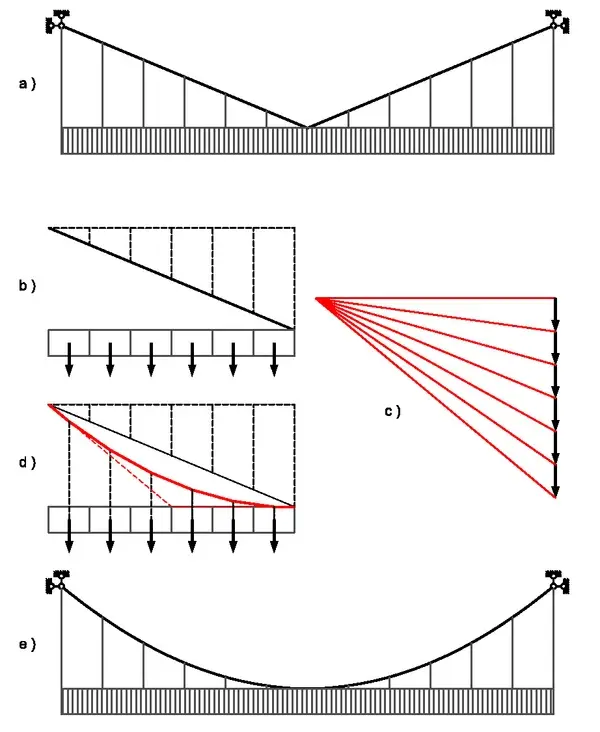

At the beginning, we can imagine the cable taking the simple shape shown in Figure a, which looks like an inverted triangle.

Because the structure is symmetrical, we only need to analyze one half of it.

As shown in Figure b, we can divide this half into six equal sections, each representing an equal portion of the total load — a process similar to the idea of calculus, where continuous loads are approximated by small discrete parts.

In Figure c, we draw the force polygon that corresponds to these six equal loads. Then, in Figure d, the red broken line represents the “cable polygon,” which shows how the forces are distributed along the cable.

When we use this red cable polygon as the actual geometric shape of the suspension cable, we obtain the smooth curve shown in Figure e.

Because the load is uniformly distributed, this shape is already the most efficient one — no further adjustment or iteration is needed. Even if we repeat the process, the result would be exactly the same red curve.

Therefore, this red curve represents the optimal shape of a suspension cable under uniform load.

It carries pure tension without any bending moment.

It’s important to note that this curve is not a catenary, but rather a parabola, because the load it supports is uniformly distributed horizontally (the bridge deck), not along the cable’s own weight.

The Mathematics Behind the Curve

The shape of a suspension cable has fascinated scientists for centuries:

- Aristotle once thought falling objects followed straight and then downward paths.

- Galileo corrected this with the concept of the parabola but mistakenly believed a hanging chain also formed a parabolic shape.

- Later, Jungius clarified that only a uniformly loaded cable (like a bridge deck) forms a parabola.

- Finally, in 1691, Leibniz, Huygens, and Johann Bernoulli independently derived the true mathematical expression of the catenary curve.

This progression mirrors the way human knowledge evolves — from observation to correction, to mathematical precision, and finally to engineering application.

Engineering Practice: From Equations to the Real World

Suspension bridges don’t only face vertical loads — they must also withstand lateral wind forces.

In 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapsed in the wind, reminding engineers of the importance of aerodynamic stability. Modern suspension bridges, such as Japan’s Akashi Kaikyo Bridge, have since incorporated sophisticated wind-resistant designs.

The Akashi Kaikyo Bridge used to be the world’s longest suspension span at 1,991 meters — originally designed for 1,990 meters, but the 1995 Kobe earthquake stretched the towers one meter apart.

From Theory to Masterpiece

From the mathematical study of curves to the construction of kilometer-long spans, suspension bridges represent the perfect fusion of science, mathematics, and engineering creativity.

They are proof that the most elegant solutions often arise from the simplest principles — in this case, the power of tension.

In the hands of skilled engineers, mathematics becomes art, and every suspension bridge stands as a monument to both human reason and imagination.

🏗️ Related Reading