When we look at elevated highways or viaducts, one curious detail often stands out — the bridge piers are huge and solid, yet the part that actually connects to the bridge deck is very small. Why would engineers design such a large structure to rest on such a limited contact area? Does this make the bridge less stable, or is there hidden logic behind it?

In this article, we’ll break down the reasoning behind this design — exploring how bridge bearings work, why contact areas are minimized, and how this balance between rigidity and flexibility keeps bridges safe and stable for decades.

1. Basic Structure of a Bridge

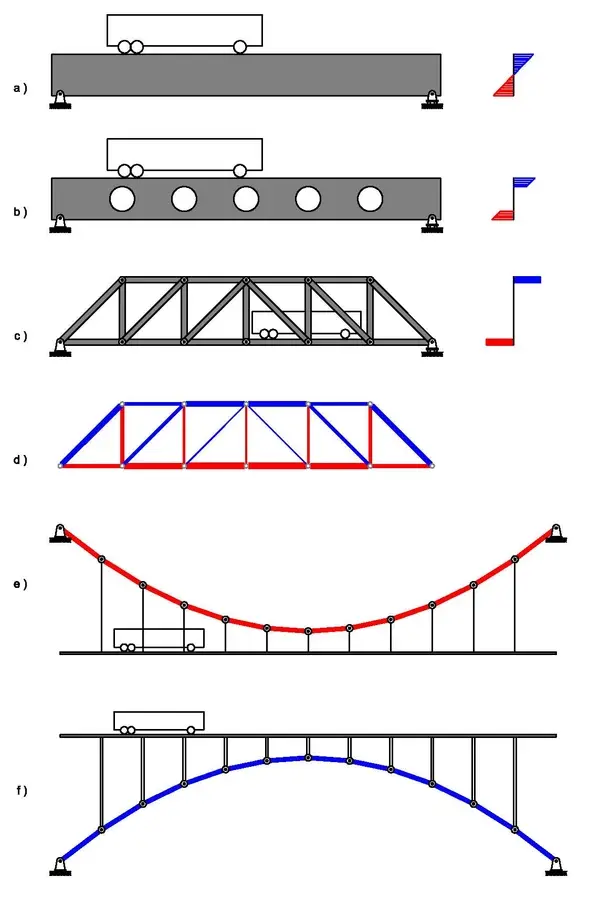

A bridge typically consists of two main parts:

- Superstructure (Deck System): the part that carries vehicles and pedestrians.

- Substructure (Piers and Foundations): the part that transfers loads to the ground.

Between these two lies a crucial component — the bridge bearing.

Bearings act as the interface that transfers vertical and horizontal loads from the superstructure to the substructure, while allowing limited movements caused by temperature changes, traffic loads, and material deformation.

2. Why Is the Contact Area So Small?

At first glance, it might seem that a larger contact area between the bridge deck and pier would make the bridge more stable. But in structural design, the goal is not just stability, but controlled flexibility.

A smaller contact area at the bearing allows the bridge to move slightly — and that movement actually protects the structure from damage.

(1) Efficient Load Transfer

Bridge bearings concentrate vertical loads and transfer them precisely into the pier.

If the contact surface were too large, uneven settlement or material deformation could cause parts of the surface to lose contact, leading to stress concentration in unpredictable areas.

By keeping the contact area small and well-defined, engineers ensure that loads are transmitted efficiently and predictably.

(2) Flexibility for Deformation – Preventing Structural Cracks

This is one of the most misunderstood aspects of bridge design.

Bridges are not completely rigid — they constantly expand, contract, and flex due to temperature changes, heavy traffic, wind, and even slight ground movements.

If the deck were rigidly fixed to the pier with a large, immovable surface, these natural deformations would create internal stress at the joint.

Over time, this stress could lead to cracks at the bottom of the bridge deck, or even at the connection point between the deck and the pier cap.

By using a small, flexible bearing area, engineers allow the deck to rotate slightly and slide a few millimeters in response to temperature and load changes.

This controlled movement releases stress that would otherwise build up in the concrete or steel — effectively preventing cracks in the bridge deck and supporting girders.

In short:

The small contact area is not a weakness — it acts like a “joint” that lets the bridge breathe.

(3) Temperature and Material Adaptability

Materials expand when heated and contract when cooled. On a long bridge, this can mean several centimeters of total movement.

Bearings with small, smooth contact areas allow that movement to happen freely without creating pressure on the pier or deck.

A large fixed contact surface, by contrast, would restrain the structure, forcing temperature stresses to accumulate until the concrete cracks or the joints deform.

(4) Easy Maintenance and Replacement

Bearings are designed as replaceable components.

Their smaller size makes inspection, replacement, and lubrication much easier — essential for maintaining long-term bridge safety.

3. Why Are Bridge Piers So Massive?

If the bridge deck only touches the pier through a small bearing area, it’s natural to wonder — why do the piers themselves need to be so big?

The answer lies in the different types of forces acting on a bridge.

While the small bearing manages vertical load transfer and flexibility, the massive pier is what gives the entire bridge its stability and resistance to external forces.

(1) Resisting Horizontal and Dynamic Forces

Bridge piers are not just vertical supports — they also act as anchors that resist horizontal forces caused by wind, traffic braking, water flow, and even earthquakes.

When a heavy truck brakes on the bridge deck, a large horizontal force travels through the bearing into the pier.

A massive pier provides enough mass and stiffness to absorb and spread that force without tipping, bending, or vibrating excessively.

If the pier were slender, it could deform under repeated horizontal loads, leading to fatigue cracks or even structural instability.

(2) Ensuring Global Structural Stability

The pier forms the main connection between the deck and the foundation.

Its size and shape ensure that all vertical loads from the deck are evenly distributed through the pier and into the ground

A larger cross-section gives the pier higher buckling resistance — meaning it can carry very large compressive forces without deforming.

This is especially critical for tall viaducts, where slender columns could sway under wind or seismic action.

By increasing the pier’s size and weight, engineers lower its natural vibration frequency, helping the bridge resist resonance and oscillation during earthquakes or strong winds.

(3) Enhancing Safety During Seismic Events

In earthquake-prone regions, the pier acts as the energy-dissipation component of the bridge.

Its mass and ductility help absorb seismic energy transmitted through the bearings.

A larger, reinforced pier prevents sudden failure and ensures that the bridge remains standing even if minor cracking occurs.

In short — the pier is designed to sacrifice itself first, protecting the deck and keeping the bridge functional after a quake.

(4) Balancing Rigidity and Flexibility

While the pier is designed to be strong and stiff, it must still work harmoniously with the flexible bearings above.

The pier provides rigid support against vertical and horizontal loads, while the bearings introduce controlled flexibility to accommodate small rotations and movements.

This combination — a massive, stable base and a small, flexible interface — is what keeps the bridge both strong and adaptable.

It’s the same principle used in modern earthquake-resistant buildings: rigid below, flexible above.

(5) Aesthetics and Safety Margin

Finally, large piers also serve practical and aesthetic purposes.

From a safety perspective, engineers design with redundancy — ensuring the pier is strong enough to handle unexpected overloads or impact forces.

Visually, a robust pier conveys stability and trust, reassuring drivers that the bridge is secure.

In Summary

Bridge piers are massive not by coincidence but by necessity.

They resist vertical compression, horizontal thrust, vibration, and seismic forces — all while serving as the stable foundation for a constantly moving superstructure above.

The small bearing area allows movement; the large pier ensures stability.

Together, they create a balanced system — one that can stand for decades under heavy traffic, temperature changes, and natural forces.

4. Types and Functions of Bridge Bearings

Bearings come in different designs, depending on movement and load requirements:

- Fixed Bearings: allow rotation but prevent horizontal movement.

- Expansion or Sliding Bearings: permit both rotation and limited movement, accommodating thermal expansion.

- Elastomeric Bearings (Rubber Bearings): absorb vibrations, support movement in multiple directions, and enhance bridge flexibility.

Each type ensures that the bridge can adapt to natural deformations while maintaining strength and stability.

5. The Engineering Balance: Rigidity and Flexibility

The “big pier, small contact” design reflects a key principle in structural engineering — balance.

Bridges must be strong enough to resist external forces but flexible enough to adjust to environmental and mechanical changes.

A large pier provides stiffness and strength, while the small bearing area introduces controlled flexibility. This delicate balance is what keeps modern bridges standing strong yet resilient over time.

6. Conclusion

The small bearing area isn’t a weakness — it’s an ingenious engineering solution.

By concentrating load transfer, allowing movement, and ensuring adaptability, bearings serve as the silent guardians of bridge stability.

So next time you drive over a massive elevated bridge, remember: beneath that huge pier and small bearing pad lies decades of engineering wisdom — a perfect balance between strength and flexibility, stability and adaptability.